| Retour

Independence day 4 july 1943 The B-17 flying fortresses shot down in our region and the fate of their aircrews. | In

the course of two years spent researching the events that took place on

this sunny summer day of July 4, 1943, "Independence Day" in the USA,

the information gathered came from four different sources: the most

productive came from contacts with the persons involved: first the

surviving airmen themselves, second the US Archives at Maxwell Air

Force Base in Alabama, then reference documents or general information,

and finally various personal contributions from researchers specialized

in studies of air combat. The presentation of this article has been

voluntarily simplified in order to keep the essential elements tied to

these evasions . . . the long and dogged odyseey of men bent to escape

capture at any cost, with the help of compassionate souls, either

volunteers or members of various patriotic networks. A human adventure

with only one goal: returning to Great Britain, the only free land in

occupied Europe. One should recall first that, in every case, the

tragic events that took place in the life of their inhabitants and

their painful consequences have been related on various occasions by

the local press. In the present case, the main purpose was to relate

the unknown part of this adventure, that is the long and difficult

journey back to their base or their country for the airmen who had

survived this "Independence Day". On

that day, July 4, 1943, as the formation of B-17 flying fortresses was

on its way to their target, several dramas were taking place in the

skies of the Orne and Sarthe departments, virtually at the same moment.  Let us resume the facts:

One hundred sixty B-17 flying fortresses from bases in the South East

of England are dispatched on this Independence Day towards targets

defined by the US Air Force headquarters. Among them one hundred are

heading towards the Gnome and Rhone factories which manufacture engines

for the German Fockewulf planes. The sixty others have for targert the

flood-gates of La Pallice. Several other nearby installations are also

targeted, including the train station in Le Mans and the adjoining

airdrome. One this Summer day - a Sunday - the townsfolk who witnessed

this drama remember that the sky was blue and clear during the flight

of the US Air force formation, and yet the Thunderbolts and Spitfires

accompanying the fortresses would be prematurely recalled by their base

because of deteriorating meteorology conditions in Great Britain.

Certainly a handicap for the heavy bombers deprived of assistance. . .

in case of a confrontation with the German fighters always on the

lookout. According to the American archives now available, the first

part of the raid went without any noteworthy incidents and the pilots

stated that they had reached their respective targets.

|  | B-17F 42-29960 "Nymokymi" in June 1943. |  | The

wreck of "Nymokymi" in Belfonds. These are the only existing photos of

the wreckage taken by Roger Cornevin, July 5 in the morning. | | Near

Le Mans German flak targets and hits a first fortress. In the distance

a swarm of German fighters are getting ready to attack. . .

The

right outside engine of the fortress "Nymokimi" of Lieutenant Gordon

Erikson has just been hit broadside by flak and the propeller is

feathered. The plane is distress, trailing a long wake of black smoke,

reaches the small episcopal town of Sees as the formation is flying

back to England.

It is noon. The parishioners are walking out of

the cathedral. The Ormeaux Stadium field, usually occupied by the

Werhmacht, is vacant today for the local and regional athletic teams.

Everyone is watching the fortress desperately trying to reach Grafton

Underwood, North of Bedford, the most Western base in East Anglia she

had left from two hours earliers, but it is no longer possible. . . The

pilot Gordon Erickson stated later: "with one engine

disabled, we were trailing behind the formation heading North. The

German fighters, on the lookout, rush towards our now disabled and

isolated aircraft. The oxygen circuits which allows us to fly at more

than ten thousand feet are destroyed by a murderous enemy fire. I give

order to bail out. On board the fire is raging and the crew rush to the

emergency exits. We have great difficullties opening the evacuation

traps. . . My overalls catch fire and I try to put it out with my

hands. As a last resource I go to the emergency exit to

the front, and I jump out behind the mechanic. The icy cold air blowing

through the ejection trap finally put out the flames which were slowly

burning my overalls. Below me I see five white corollas. . ., green

pastures. . ., a river and a cathedral in the distance. I land, unhurt,

on this foreign soil, my parachute caught in the branches of an apple

tree. . ., my feet barely touching ground. Some villagers run toward me

to help. . ., I remove my equipment: parachute and Mae West. Quickly I

use my pocket knife to cutt off the straps of my parachute. I take

cover in a double row of hedges and soon three other members of my

crew, burned on their hands and face, join me here". In fact

eight airmen had parachuted on the Belfonds plain in an area between

the hamlet of Conde le Butor and the church of Cleray. Two airmen had

stayed aboard: bombardier Donald Irvine fell with what was left of the

machine-gun turret at a site called "Chene d'amour" (oak of love) near

Belfonds, and navigator Francis Hackley, his parachute in flames, fell

at "Val d'enfer" (vale of hell).

Two crewmembers did not escape

capture in spite of the quick intervention of the townsfolks and

members of the local resistance, among which were Edouard Paysant,

Departmental Chief of the BOA and Victor Chevreuil, Mayor of Mortree.

The six survivors, comrades of misfortune, will split into two groups;

Lt pilot Gordon Erickson and three crewmembers will be sheltered in a

barn near the village of Belfonds. The two wounded men, Willard Freeman

and Charles Mankowick will be taken on stretchers by the local

Resistance first to a shelter and then to the Forest of Gouffern near

Aunou le Faucon. A hut made of branches, hidden deep into the forest,

will be their shelter for three weeks during which they receive the

necessary care. "our hut was not very watertight but it was sufficient

to shelter us in August. Two doctors came by regularly to check on the

progress of our recovery" Freeman stated later.

Six months later,

after spending a few nights under the stars, followed by a long stay in

the Lyon region to regain some strength, our two convalescents will

reach England and their respective base in December 1943. Gordon

Erickson, accompanied by Sargeants Ashworth, Penly, and Wingerter, will

attain Gilbraltar at the end of August 1943 after an eventful journey,

crossing Basque country without any major problem except for a scary

moment in Dax caused by the inquisitive look of a German agent puzzled

by the shoes our travelers are wearing. Alarming suspicion which

worries our evadees and make them fear the worse. Will their false

identity papers stand up to close scrutiny?

After a long dialogue with the agent, their experienced guide finally get them out of this delicate situation.

At last our evadees cross the border in a truck carrying. . . baby

chicks. Soon after, they reach Bilbao and finally freedom at the

British Consulate here. After the crossing of the Pyrenees and their

arrival to Gibraltar where they are taken in charge by the RAF, our two

wounded men, Freeman and Mankowick, now fully recovered, announce their

safe arrival as soon as they reach London by transmitting the following

message on the BBC: "the friends of the little forest have arrived

safely". What a relief for all the resistants and their helpers in the

Sees, Montree and Argentan region, who had worked to ensure their

evasion, at the risk of their own lives.

Other infos on this crash: http://www.384thbombgroup.com/pages/erickson.html | |

Willard Freeman |

Gordon Erickson | | (Collection Didier Cornevin) | (Collection Didier Cornevin) |  | | Grafton Underwood, Airfield of the 384 BomberGroups, today. |

| On

the same day and at the same hour, the village of La Coulonche North of

Juvigny-sous-Andaine witnesses a similar drama. The flying fortress

flown by Lieutenants Olaf Ballinger and John Carah suffers the same

fate, crashing at "Val de Vee" in the Andaine Forest. John Carah: "I

had not realized that we did not have any more oxygen and that the two

tail gunners had been killed during the attack by the German fighters.

The elevator jammed and it was impossible to pilot the plane. I jumped

out, remembering the massacre in Antwerp when the parachutists had been

taken for targets by the German fighters. At the emergency door was

Llieutenant Williams, his unfolded parachute in his arms. . . I told

him to jump no matter what. . . but he refused. Huge emotion! While

coming down, a fighter feigning an attack swooped down on me and scared

me to death. . . Then I saw our flying fortress get into a spin while I

desperately scrutinized the ground below to finally spot an apple

orchard. I barely managed to avoid the fork of a tree. I remained in

hiding in the woods for seven hours while observing the surroundings

and the comings and goings at a farm before taking the risk of showing

myself to the farmer. A carafe containing a clear liquid caught my

attention. . . Thirsty, I gulped a glass of calvados. . . I had

mistaken for water.".

The crew had lost three of

its members: the two tail gunners killed in flight and Lt Williams who,

desperate, decided to jump. . . too close to the ground. Why did he

wait so long? Remembering having seen him jump out of the front hatch

at the last minute before the explosion on the ground, John Carah to

this day still wonder why. . ..

Two crew members were taken

prisoners then taken to "Stalag Luft" reserved for Allied airmen. Taken

in charge by a young guide and with the help of an organized Resistance

network, John Carah will leave for Switzerland after having been

sheltered near Lassay, in the Mayenne region, by the Breteau family.

Provided with a fake identity card in the name of. . . Jacques Dupont,

business representative, he and his companions take any means of

transport available on the way. . . train, bus, Petain Youth's camp

truck, hitch-hiking. Finally it is a trek on foot through the pine

forests, pursued by patrol dogs guarding the border. Our little group,

treating themselves to the luxury of a sympathetic taxi driver will

attain Berne incognito via the verdant shore of the Lake of Neuchatel.

The stay of John Carah in Switzerland, in relative freedom, could not

last very long. He takes the risk to leave Swiss neutrality and

attempss, once again, to cross the border. . . to occupied France. . .

Incarcerated with his travelling companions by the Gestapo, they are

freed, without having to put up a fight, by the local Resistance after

a brisk exchange of fire. John reaches Spain totally exhausted after

the difficult crossing of the Pyrenees. At last, he perceives from afar

the lights of Figueras!

We bring the attention to a final thought

in the testimony of this pilot aided by volunteers helpers and

Resistance members: "I take this opportunity to express my

utmost admiration and gratitude to the various French Resistance lines.

Every hour of the day they risk their lives so that a great numbers of

shot down airmen could return to combat and thus perhaps shorten the

length of the war".

Another epic tied to this

crash in La Coulonche is the one of pilot Olaf Ballinger. Exhausted and

lagging behind, he is unable to follow the same pace as his travelling

companions. Thus he will barely escape their fate when they are caught

in an ambush. In the pale dawn lighting the foothills of the Pyrenees,

exhausted and his clothes in tatters, he reaches the first houses of

the Andorre region. Sustained by the will to reach his goal at any

cost, he takes a needed rest in a village which seems uninvolved in the

torments of war. He will face the first cols in the wake of a group of

smugglers carrying bales of tobacco. Then after a temporary captivity

in a jail in Manressa, he reaches the British Consulate and finally

Gibraltar on December 4, exactly five months after the crash in La

Coulonche. | |

| | left

to right: McConnell, navigator; Bollinger, pilot; Williams, parachute

opened in the plane; John Carah, copilot. | | Credited

with having shot down one enemy fighter, Paul McConnell is helped by a

forester in the Andaine Forest. He spends a few days in hiding at the

"Ermitage", a manor situated North of Juvigny -sous-Andaine and then he

is taken in charge by Andre Rougeyron. It is at this time that he is

reunited - unexpectedly - with another crash survivor, William Howell.

Young machine gunner Howell, hastily dressed as a boy-scout, sporting a

Basque beret and carrying a basketful of vegetables for the sake of the

cause, arrived at the "Chalet du Brouillard" (Andre Rougeyron's home in

Domfront) in a horse drawn carriage. With the help of some Calvados, he

endures without complaints the extraction of schrapnells from his back.

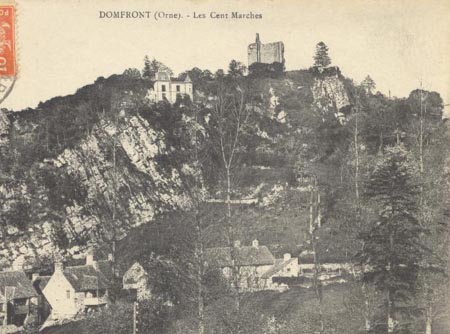

| | "The chalet of fog" in top where many aviators was hidden by André Rougeyron in the public garden of Domfront. | An

opportunity will come up for Paul McConnell and William Howell to try

an escape with the Brittany line. But the plan organized in Quimper by

the local Resistance, in coordination with a speed motorboat and a

British submarine off the coast of Ouessant will not succeed. The radio

operator in charge of communications with England had been identified

and killed. However, they will have to make the best of it and return

to Paris to wait for a second opportunity. Reluctantly Paul McConnell

and William will part company. Howell will go on to Perpignan where he

is taken in charge by some unscrupulous guides who will make him and

his evadee companions go round in circles near the border. After the

Christmas holiday it is at last the successful crossing of the

Pyrenees, then on to Gerona, Barcelone, Madrid, and finally Gibraltar

in February 1944, seven months from the date of the crash in La

Coulonche.

In desperation, the Resistance decides to turn over the

navigator Paul McConnell* to the "Comete" line an organization where,

for each escape, one courageous patriot would pay with his life. Train

to Pau, a stop at a Basque farmhouse, frequent change of guides, a long

march without respite in the bitter cold before reaching, exhausted, a

Spanish farm. Then a stay in a jail where some thirty prisoners evadees

- crash survivors and German deserters - are awaiting for the Spanish

authorities to decide of their fate. At last it is the much awaited

welcome of the United States Embassy, then Gibraltar, and finally one

last stop,Scotland, and the return to the United States on March 1,

1944, that is an eight month journey since the crash in La Coulonche.

|  |  |

| | McConnell, navigator | Owens, Bollinger (center) and the family who hid them. | Owens, Gunner. | | Machine-gunner

Owens, another miraculous survivor of the crash at Val-de-Vee, would

not escape destiny. After being sheltered by Geslain, a farmer in St

Opportune, he accompanies Ballinger and his group part of the way on

their journey. His body will be found in the mountains and the cause of

his death will remain a mystery. There are various explanations . . .

he was killed by a border while crossing the foothills of the Pyrenees

or he died from exposure to the elements.

|

|  | | Paul

McConnell, in leather jacket and John Carah, with the blue cap, at the

time of the ceremony of Belfonds in 1999 | |

| During

this same raid, at the same hour, two other flying fortresses were shot

down in the Sarthe region, West of Le Mans. Machine-gunner David

Butcher will be the only surviving crew member. His fortress "Lakanuki"

is hit by flak and explodes in flight. Panic. . . surviving instinct. .

. almost unconscious, he finds himself, miraculously, parachute opened,

above the village of Poille sur Vegre. "What a bizarre feeling!" he

will say later. Two providential villagers help him slip away. . . by

bicycle. Clandestinely employed as a "deaf and mute" gardener and later

on unwillingly draftet in the local Resistance network, he takes part

in receiving the arms parachuted by planes supplying the maquis. His

adventurous journey in French territory willl have lasted seven months.

His companions in the Resistance will have suffered various fortunes

but David Butcher, lucky in spite of himself, thwarted all the ambushes

set on the way. He kept undying memories of his stay on French

territory . Today he is honorary citizen of Poille sur Vegre.

| |

|

| | Alfred Auduc, chief of the local Resistance and belonging to the "reseau Buckmaster" . | David

Butcher, alone survivor of the crash of the Fortress "Lakanuki" and

Alfred Auduc. |

| Noon

and the twelve strikes of the town clock chime in the quiet countryside

of Noyen Malicorne Maezeray area. The inhabitants go about their work.

A fourth fortress, the "Mugger", hit by flak, crashes. A witness

notices in the distance "the parachutists coming down and trying to

avoid the areas in flames on the ground". The fire spreads. All are

fighting the blaze: the Werhmacht, the gendarmes, the firemen, and the

townsfolk. . . One

of the airmen lands on the roof of a hangar, another near a German

encampment. The latter will relate: "I had landed in a wheatfield just

harvested. No way to hide. I noticed a wooded area nearby. I heard

gunfire and saw two German soldiers running toward me gun in hand. I

had suffered serious burns on my hands and face. . . and I was

bleeding". Among the ten crew members: two killed, two taken prisoners,

and six evadees who will manage to slip through the net spread by their

pursuers. But once again it is a tragedy heavy with consequences for

the townsfolks among which some, as it happened in our little town of

Sees . will know deportation.

|

| Leaving

this very day the airfields of East Anglia sixty other B-17 flying

fortresses are flying in direction of the locks of La Pallice. Four

other fortresses will be shot down by flak and German fighters at the

following points: Island of Oleron (Charente Maritime), La Gueriniere

(Vendee), St Colomban (Loire Atlantique) - The following link tells the history of this fortress:https://b17-saint-colomban.ovh - and the Bay of Biscay. A ninth fortress will make a forced emergency landing upon her return to Great Britain.

Before

rejoining their respective bases in Great Britain, the airmen who have

survived the crash of their plane in our region on this Independence

Day have endured, as many others have, the dangers of aerial combat,

the resulting terrible emotion and lastly. . . the jump into the

unknown on a territory full of traps and pitfalls after having bailed

out of their disabled aircraft. All these dramatic events are generally

followed by an uninterrupted manhunt in the woods, the towns, or the

countryside.

It

is often possible to bring together a view of the facts and events, if

one consider the dangers incurred, with the testimonies from the

Resistance members and all the others - patriots, those who gave

shelter, the anonymous volunteer helpers - met by chance in a forest

and having participated in the rescue and life-saving operations at

their own risks and perils. Roger Cornevin, Association Normande du Souvenir Aérien 39-45 Translation by Marie Antoinette McConnell | |

| | Localization

of the crashs: 1 Belfonds; 2 la

Coulonche; 3 Poillé sur Végre; 4 Malicorne | |

| | Roger Cornevin and his brother on the wreckage of a Me 109 shoot by Flying Fortresses, July 4 1943. | | *

After the failed escape attempt off the Brittany coast, Paul McConnell

returned to Paris where he was sheltered by Resistance members -

Raymonde Chassagne in Paris and Lucienne Fevre in Pavillons-sous-Bois

(shortly after Paul McConnell's escape , Raymonde Chassagne was

arrested by the Gestapo and sent to the concentration camp of

Ravensbruck). On December 24, 1943, another escape attempt was aborted

when the line had been infiltrated and most members arrested.

Sources:

Personal letters with the allied aviators, Archives of the Usaaf,

"Agents d'évasion" of André Rougeyron. Cahiers flêchois 1995. | Thank you to ask for the author's authorization for a partial or complete publication of this narration | | Retour |