|

“I

have consulted a number of French and foreign archival files (

United

States

Air

Force and Royal Air Force) and gathered together many precise

details (which you will find in italics) that are necessary to

explain and understand the events from my wartime journal.”

Roger

Cornevin-Hayton

Excerpts

from my “Journal of Youth,” May to August, 1944.

June

10, 1944: In the distance, the clock tower in Bursard…

The

bad weather persisted and the black clouds were ominous. Our

gazogene-powered taxi from the Septier house puttered down the

small country road. We saw in the distance the bell tower in the

round roof of the Town Hall that was to be our future home.

Bursard,

a small village located six kilometres from Sées, welcomed us

in the silence of the blue-green countryside, shrouded in mist

from the

Perseigne

Forest

. Long rows of well-aligned white fences

announced the boundaries of the stud farm, “Haras de Bois

Roussel.” where we took refuge in May and June 1940. Our lives

could have proceeded peacefully, like a long, quiet-flowing

river, while waiting for war to pursue its course, but in the

relative calm of our pastoral retreat, an inexplicable unease

seemed to develop around us.

People

had spoken about the establishment of several aerodromes in the

areas of Essay, Lonrai and Semallé, several kilometers away

from our temporary home. It was rumoured that local residents of

these neighbouring villages had been conscripted by the Todt

organization to lay the foundations.

The construction of such aerodromes by the Luftwaffe

could only attract the attention of Allied bombers, who were

always on the alert.

Ventes-de-Bourse,

Mesnil Brout as well as the railway lines at Forges, Vingt

Hanaps, Saint Gervais de Perron and others were the daily

targets of the RAF and USAF.

Each

day brought its share of unexpected events and diversions.

These

were unsettled days. Some days I did not see anything and felt

pretty much in the dark about things. What good would there be

in maintaining a journal? Only one thing, the bad weather and

the formations of planes, passing above the clouds, Allied

aircraft pitted against German fighter planes, especially the

Focke-Wulfs and Messerschmitts based in the surrounding

aerodromes.

The

American Air Force was active by day and the RAF bombed at

night. The incessant noise of the armadas of aircraft passing

over our heads at night disturbed our sleep.

P47s,

with their black and white striped wings, flew over us at very

low altitude and we waved handkerchiefs as a sign of friendship.

We had the impression that the pilot in his cockpit tilted the

wings of his plane so he could see us better and we were filled

with enthusiasm when it seemed he had understood our signals.

The Allied pilots flew very low…possibly at a height of 50

metres. Curiously, they seemed to have taken the town hall as a

point of reference before attacking their prey, in this case the

German fighters preparing to take off.

June

10, 1944

:

We are not alone any more!

On

this day I had the earphones of our rudimentary crystal radio (which

my family made to hear the reports from the BBC) pressed tightly

to my ear. Jean Marin, Robert Schuman, and Pierre Dac were our

heroes. They were in

London

, on the other side of the Channel; it made

us dream. Suddenly, an alarming movement…the moon-shaped face

of a German soldier was pressed against one of the window panes

of our classroom. What had brought him so near?

The

next day, heavy trucks pulling guns, undoubtedly for the DCA,

surprised us as we were eating our lunch. The feldwebel

had reason to be here; it preceded the encampment of a group of

gunners under the lime trees near the town hall. This intrusion

into our quiet countryside filled us with concern.

|

|

|

The small village of Bursard, in the department of Orne. Isolated to the left, the town hall where will live the Cornevin family. She will cohabit some times with the servers of a battery of Flak. Its cannons will come to camouflage themselves under the limes of the alley of the town hall.

|

|

|

Ten

trucks, towing guns covered with camouflage netting, lined up in

the shade of the

tree-lined alley. We realized our peace in this place was over,

knowing this unexpected presence was likely to intensify

attention from Allied aviation. We confirmed

that, if an Allied plane flew low over our heads, any movement

on the ground would draw a burst of fire.

Recovering

from our surprise, we had no alternative than to hide the

unwieldy crystal radio set and the compromising photographs

highlighting the past military service, in the Air Force, of our

cousin who was demobilized in 1940. One photograph represented

his plane, a Potez, on the ground at Auxerre, lost in the middle

of a herd of sheep.

At

that moment, our cousin did not have a plane any more, but his

memories of Africa

had the gift of making me dream. It was the

exotic image of Gao on the

Niger

and the unleashed dreams of desert sands...

What

were the intentions of the non-commissioned officers in this [flak

battery] company? Several days passed.

Each brought its own speculations. The news was like the

weather…good and bad. To our great surprise, our occupying

force tried not to disturb us too much and passed their early

days in the classrooms and the kitchen, without really wanting

to inconvenience us. They had not yet discovered, on the second

floor, my brother’s and my hiding place where were hidden all

the crystal radio sets of the inhabitants of Bursard that were

to be gathered up by order of the Kommandantur.

We did not play in the same places as the grown children;

our passion was hunting with our two dogs for ducks and water

hens on the riverbanks and in the ditches bordered by reeds at

the stud farm at Bois Roussel.

One of the German billets taught us how to identify the

planes from the R.A.F or US Air Force, starting from silhouettes

printed on a booklet. The silhouettes and the characteristics of

these planes flying high in the sky soon held no mystery for us.

One evening, some drunken soldiers started a ruckus in the

courtyard. Prudently we keep our distance…

June

12:

Disappearance of the batteries...

Today,

there were attacks by Mustangs, planes easy to identify with

their square wings. We began to understand the reasons behind

the activity around us. Several aerodromes were under

construction in the surrounding villages. We learned that five

soldiers of the group (who were dispatched to the area around

Essay to get the aircraft ready) were killed or mortally wounded.

A

beautiful morning... relief... without warning, the trucks

disappeared from the village dragging in their wake their

threatening guns. But they set up only a few hundred meters away,

in the green meadows of the stud farm at Bois Roussel, at the

spot called "Les Fontaines." Scarcely visible beneath

the branches, it was very difficult to make them out from our

house, in spite of the fact that the meadows in the south of

Bursard were very open, practically without obstruction. The

thoroughbreds did not seem to be overly disturbed by the

presence of these intruders.

June

13:

A fighter crashed on the railway.

Aerial

combat near Semallé and Neuilly-le-Bisson. Two planes crashed

in a spiral. Nationality unknown.

In fact, one plane was the P47 of Lieutenant Bentley

(originally from

Oregon

) whose

plane, caught by the blast resulting from the explosion of a

rail car, struck the railway line at Vingt Hanaps. The burned

body of the pilot remained there for a long time. Mr. Bernard

Pottier of Neuilly de Bisson has personal mementos and wishes to

return them to the family of Lt. Bentley, or his descendants.

June

17:

The ground of Essay becomes a target...

A

deafening noise in the distance. Heavy clouds skim over the

ground. The terrain around Essay became a target. The gunners

billeted within our walls identified formations of the

four-engined Liberator

bomber.

The

unfavourable wind muted the sounds of the bombardment. A muffled

but persistent noise …

May

and June 1940 -- We had already taken refuge at the stud farm at

Bois Roussel.

The

French troops had left the premises of the chateau in a

lamentable state and had killed the two swans in the pond before

their hasty departure towards the South.

Germans

on motorbikes made up the advance party of the invading army and

surprised us one beautiful morning in June, before we had got

out of bed. A din of engines under our window made us jump up

and look at the impressive spectacle of these menacing-looking

motorcyclists, wearing gray raincoats, covered in dust. After

a fast inspection of the house, one of them sat at the piano and

played war songs.

Note:

in La Luftwaffe face au débarquement allié by Jean

Bernard Frappé, the testimony of a German pilot "On June

17 a little before

1 p.m.

the

German pilots were surprised by a score of Mustangs who

succeeded in cutting down 3 Focke-wulfs.”

"We

had made real efforts to get organized on the ground when an

attack took to us by surprise. We threw ourselves to the ground

as all hell broke out around us. It was total chaos. An eternity

later we were all alive.

In

fact we were visited in the fading hours of the day (around

8:30

p.m.

) by 38

Liberators [bombers]; the meadows around Essay received one

hundred tons of bombs, which reached their target. Twenty-five

other B25s attacked the area occupied by the I /JG 1 in Lonrai.”

Following

this attack, which practically destroyed the landscape, the II /JG

1 could only abandon this overly-exposed site and redeployed in

the pastureland adjacent to the

village

of

Semallé

,

getting on toward Lonrai. A

narrow grass runway, bordered by high trees, was created as were

others during the days that followed in the meadows and fields

bordering the road connecting Alençon and Essay.

Today,

a dogfight which resulted in a fire at the farm at

Beauvais

.

June

22.

It

is approximately 1400 hours. In

the distance a plane spiralled into the thick foliage of the

forest at Perseigne.

Report

of Mr. Paganet of Cerisé:

“On

June

22, 1944

,

around 1430 overhead the woods of Maléfre (Sainte Peternet,) an

aerial duel which resulted in a German aircraft falling in

flames into the forest at Perseigne, at a place called "Fourolet"

(Ancinnes).

The

pilot parachuted out but was killed by mistake by his German

colleagues as he descended and before he crashed into the

crossroads at Fontaine Pesée.”

June

24:

After four days of bad weather... feverish activity among the

men at the batteries. They milled about excitedly in our

courtyard.

Aerial

combat overhead between planes of unknown nationality.

June

28: A fighter crashed near

Semallé...

A

fighter crashed near Valframbert -- English nationality,

according to some witnesses.

I

am able to bring in reports on the crystal radio about the

execution of Philippe Hanriot.

On

June 28, 1944

, a

fighter crashed near Semallé in the vicinity of the commune of

Valframbert. The pilot was buried at this location and the grave

has the following inscription: “A British aviator, identity

unknown, died on

June

28, 1944

. A

dogfight with a German plane. Plane No MN818.

Note:

After investigation, the plane at Semallé could have

been a Typhoon MN818 piloted by FO Holmes of the 609th squadron.

June

29:

Yearlings were spooked…

Note:

Bernard Frappé (q.v.) A pilot of a II /JG1 was wounded today,

June 28.

FHJ

FW Brunner of the 6 Staffel was taken as a target by two enemy

fighters as he drove along the road connecting Essay to Alençon.

Another

day, the yearlings, which were spooked by the passage of

overhead of Thunderbolt bombers flying at low altitude over our

heads, galloped past by our hiding place. We stayed flat on our

stomachs in the tall grass near a hedge; we did not dare to make

a move. One scare after another made us think of the risks that

there were in crossing these open spaces while our valiant

thoroughbreds were grazing on the tender grass of the meadow.

Aerial

combat. We heard that a German bomber had crashed into the

forest at Perseigne.

Mr.

Jacques Paganet of Cerisé, offers the following corroboration:

"On

June 23 at 2 in the morning, a German bomber crashed in the

forest at Perseigne,

a

few hundreds meters from the forestry house at Buisson.

Mr. Boissier Abel, chief of district at the time, saved a

casualty from the burning wreckage, which earned him a diploma

of recognition from the occupying army.

Five

other airmen were incinerated and perished. A sign made out of

wood, on which was written “Here there are human ashes,” was

placed on top of stones piled one upon the other. This sign

later disappeared. Mr. Bossier did that as a gesture of humanity

and not of collaboration"

July

6:

A

fight in the distance in the late afternoon.

Several planes crashed into the countryside,

approximately to the north-west of us.

July

9: In the distance, a plane fell

in flames in the direction of Larré. A parachute was detached.....

July

16:

This Sunday a bomber crashed at "Chouannerie"

An

explosion in the distance...

Many

different noises could be heard in the air. An Allied plane was

shot down by the German DCA at Bélandrie near Larré, at a

place called "Chouannerie".

According to the farmer, all seven men in the crew

perished.

It

appeared that the aircraft was going to drop supplies, weapons

and ammunition for the local Maquis. The ammunition continued to

explode all night. The same question comes up… What is the

nationality of this plane? Without question, Allied.

At

the request of the mayor of Larré, I was able to identify this

plane in 1998, with the assistance of the ANSA. They were

searching for a four-engined

Halifax

plane that was carrying weapons and ammunition. After taking off

from Tarrant Rushton airbase, it was to supply the”Goudron”

area of Radon, located within the bounds of the forest at Écouves.

Six identified victims and an unidentified 7th victim

who was found much later in a beet field under a wing flap or

aircraft door. This unidentified victim could have been a member

of the S.O.E. (Special Operations Executive).

|

|

|

|

The

Halifax Bomber |

Fires marking the site of a drop zone. |

The

cause of this crash landing was given to me in 1999 following

eyewitness testimony by the mayor of Forges. A DCA was set up in

the area of Forges, like the many others at Bois Roussel, at the

place called ‘Les Fontaines’. The Germans suspected the

presence of a parachute drop zone in this area (and in the

surrounding areas) so they laid a trap by starting several fires

to make it appear like a drop zone for containers of weapons and

ammunition.

The

pilot of

Halifax

, lured by the presence of these fires, reduced

engine speed to go to a lower altitude and prepare for landing.

The German flak left no escape route for this plane and shot it

down. The names of the members of crew were unknown for a long

time.

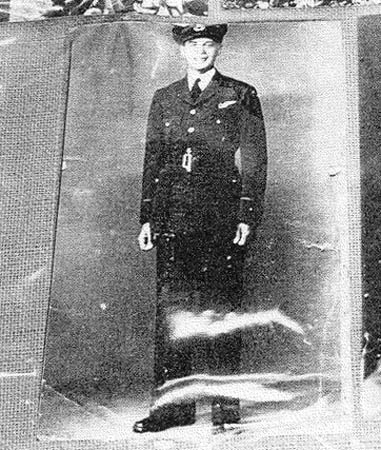

In

searching for the families, in 2003 I found Tom and Elsie

Linning on a genealogy website. They mailed me the photograph of

the one of the members of the crew, William Edward Linning, 24

years of age, Royal Canadian Air Force Squadron, 298 RAF (a

close cousin of Tom Linning). William was a flying officer,

wireless operator and machine gunner on board the

Halifax

. 60

years afterwards, they discovered William’s grave and the

circumstances of the crash. The body of William Linning (originally

from

Alberta

) rests

today with his Canadian comrades in the

Bretteville-sur-Laize

Canadian

War

Cemetery

in Calvados.

|

|

|

flying officer William Edward

Linning

|

|

Royal Canadian Air

Force

|

Other

members of crew were: P/O James Foxall Crossley (pilot, aged 24

years); Sgt. Edward Maurice Cyril Wilkinson (flight engineer,

aged 24 years); WO Joseph Wilfred Romeo Fournier (wireless

operator and machine gunner); FO Derwood William Smith

(bombardier, aged 22 years); Sgt. Enzo Biaggio Grasso

(bombardier, aged 23 years); and an airman who has not been

identified.

Thereafter,

I learned that some ten parachute drop sites had been set up

before August 1943 by Edouard Paysant, departmental chief of the

BOA (Bureau des opérations aériennes). Edouard Paysant left

his residence in Sées following the crash landing, on

July 4,

1943

, of a

B17 at Belfonds, and after he had organized and facilitated the

escape of six members of the crew (see the report "Independence

Day" on the ANSA website). Remember that the land around

Montmerrei, Merlerault, and Haras de Rouge Terres not only

received tons of ammunition and weapons, but also several secret

agents, thus preparing and arming the Resistance in anticipation

of the landings on the Normandy beaches on June 6, 1944.

Consequences...

Many arrests of members of the BOA amongst whom were my neighbor,

Albert Frémiot, Place de Parquet in Sées, and our teacher,

Jean Mazeline. After imprisonment in Château des Ducs in Alençon,

both were shot at L’Hôme-Chamodot (Orne) on

August

8, 1944

with

two other Resistance members.

Within

the context of this crash landing, let us remember the arrest

and deportation of more than 20 inhabitants of Sées and the

surrounding area, including four gendarmes of the local brigade.

July

18:

Aerial combat. For us it was an ongoing spectacle. The problem

was that we never knew which side was the winner.

July

20:

A transmitter set in the forest...

A

neighbouring farmer (I never learned his identity), who was a

little tipsy and in a state of panic, arrived at our residence.

He had just found a machine that he could not identify in the

nearby forest. Out

of curiosity, we followed him carefully. The least crackling of

the dead branches underfoot in the silence of the forest

frightened us. No Germans were in sight as the farmer led us

along paths, in shade and half-light, toward the place in the

woods at Léguernay where he found the machine. A white mass was

visible under the branches. At last, to our astonishment, we

discovered under cover of the large trees, a parachute partially

covering a signaling station. Several tubes are broken, and the

glass was scattered on the dead leaves. Our guide attests as

follows.

"Fearing

the device might explode, I hid behind a tree, took a stick and

poked at the box attached to the parachute.

Result... I saw a completely ruined, unusable radio

installation. It was

undoubtedly a radio transmitter, intended for use by local

resistance workers, but one which could never be used.

The

following day two men with serious faces and grim mouths loomed

out of the darkness as we were eating our evening meal. Their

demeanour made us feel uneasy. With carefully-worded questions,

they asked whether we knew anything about the parachute drops in

the surrounding area. We hesitated ….were they Gestapo or

Resistance? This uncertainty brought on by understandable

caution, encouraged us to remain mute in the face of such

precise questions. The unknown men departed, discomfited and

suspicious.

With

the passing of time, I remain convinced that this ruined,

parachuted transmitting set we had found was intended for the

Tessier de Tanville group which had taken refuge in Vingt

Hanaps. We know today that this group, faced with the threat of

an operation [raid] at Tanville, had been obliged for reasons of

safety to leave the place. The mayor and an inhabitant indeed

had been just shot by Germans.

This

group, established at Vingt Hanaps, had to move once again

because of proximity to the airfields of Lonrai and Semallé.

This

was an enormous loss for the Resistance whose quality of radio

communication with the services of the RAF was one of the

measures of success of the missions of supplying weapons and

ammunition. Indeed, the purpose of these night parachute

missions was to provide weapons and ammunition to the Resistance,

within the framework of the plan "tortois”, who were

ready to act following the declaration of the landing by allied

troops...

Ménil

Erreux (note in the area of Essay, by Mr. Paguenet Jacques)

“At

Menil Erreux, which was near the various trunk roads and the

railway lines, military operations were reduced to a snail’s

pace.

At

the end of July, the Germans built a vast airfield (approximately

150 hectares) in the meadows near "Normanderie”, but the

Allies’ control of the skies limited use of this airfield to

only 5 or 6 days... "

July

29: A casualty......

With

his face running with blood, one of the gunners from the DCA

battery arrived to receive some first aid. During a recent

attack by a P47, while he was manning the battery installed in

the place called ‘Les Fontaines’, a shell had hit him in the

left ear. One of his colleagues made him a solid bandage.

In

the distance, rockets rose into the starry summer sky and went

down with infinite slowness.

July

30, 1944

: Sombre Sunday! Crash landing of a

Mosquito!

There

were so many stars in the sky! We slept like a log despite the

course of the events of the day before. A plane buzzed the roof

of our refuge but this time we took the precaution of sleeping

in the cellar, hoping for greater safety. A heavy explosion

caused the house to vibrate. Awakened suddenly, we did not dare

leave our shelter.

|

|

|

The

De Havilland Mosquito |

July

31, 1944

: Discovered wreck...

At

dawn, around 6 in the morning, a German gunner we knew pounded

on our door and made us understand that a plane had crashed near

the road. My curiosity prompted me to follow him and he did not

object. A thicket covering one half hectare was blackened by

flames and scattered metal pieces of the plane were still

smoldering. In front

of us, the badly mutilated bodies of the two occupants, the

pilot and the navigator, rested in the middle of a mass of

branches. With a single word, the German made me understand that

the aircraft was a Mosquito night fighter from the RAF, shot

down by the local DCA. He drew an identity card from the tunic

of the one of the victims and held onto it... could he intend to

give it to the Red Cross?

Needless

to say, this drama saddened us, since we knew that the Allies

were making progress on all fronts. The problem was to know how

our area will be freed and with what results for all of us.

The

Germans were not long in appearing. Two days later, after

collecting the bodies of the victims, they organized a hasty

burial at the edge of our garden, within a few meters of us.

In spite of our insistence, they refused to let us be

present. A platoon of soldiers was already there at the burial

site.

A

fusillade disturbed the silence of our countryside. The emotion

was overwhelming.

This

hasty ceremony proceeded before our eyes, as we stood in

silence.

This

section refers to Frank Carr, Flying Officer (VOR), aged 24

years, Royal Volunteer Reserve, of Swinton Manchester; and

Robert Henry Clark, Flight Lieutenant, aged 24 years, Royal

Volunteer Reserve (parents living in Fulham, London), both of

the 487th Squadron of Royal New Zealand Air Force.

|

|

|

|

Flying

Officer ( Nav ) Frank

Carr

|

Flight

Lieutenant Robert Henry Clark

|

|

No

487 Squadron, Royal New Zeland Air Force |

April

14, 1996

- Bursard

A

pale sun breaks through the fog... It is just

midday

.

A

plain marble gravestone, isolated in a corner of the cemetery

(on the left) with this epitaph: "To the glorious memory of

Flying Officer Francis Carr, No 148458, October 27, 1919 - July

30, 1944, and Robert Henry Clark, No 487 Squadron RNZAF,

February 16, 1920 - July 30 1944, Fallen in an aerial combat, in

the woods of la Garenne, Bursard, Orne.

RIP"

"The other

generations might possess

shame and menace. Free in years to come

a richer heritage of happiness

hey marched to that heroic martyrdom.”

|

|

|

Tomb of Frank Carr and Henry Clark, to the bottom of the cemetery of

Bursard. |

Cross situated at the scene of the crash, in the wood of "la Garenne". |

|

|

|

Commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary in 1994.

|

1st

August: An unknown General.... Leclerc

It

is a surprise! Listen to BBC. A French division has landed in

Normandy

. One name comes up frequently... Leclerc

A

distant voice is heard, despite the jamming. It announces the

disappearance of Sainte Exupéry in the

Mediterranean

. For me it is the evocation of "Southern

Mail" [Courrier Sud], "Night Flight" [Vol

de nuit], "Wind, Sand and Stars" [Terre des

hommes], and "The Little Prince" [Le Petit

prince].

August

12, 1944

: At last!

Absolute

joy... The liberation of our sector proceeded without too many

problems. On the other hand, the Germans, in their hasty

departure, spiked all the DCA batteries that surrounded our town

hall, abandoning an impressive quantity of material. Under one

of the batteries... a package of photographs fallen from a

wallet. I took it upon myself to recover them. They would

furnish my family album. On one of them, infantrymen of the

Luftwaffe pose on the gun mount for an anonymous photographer.

The gunner proudly holds a shell in his arms, ready to inject it

into the cylinder head. Memories of war in the countryside that

will never reach the families....

|

|

|

|

A cannon of Flak sabotaged by the Germans before their precipitate

departure. |

A photo memory of the servers of the Flak battery recovered by Roger Cornevin. |

|

|

|

|

Jean

and Roger

Cornevin. |

The liberators welcomed by the Norman population. |

In

Key West, Florida in 1962 I met an American officer who told me,

filled with enthusiasm, that he had taken part with the

Patton’s 3rd army in the breakthrough at Avranches, and then

in the liberation of the villages surrounding the area of

Alençon. Under the heat of an August sun, feeling the effects

of many glasses of "apple-brandy", he had not been

able to complete his journey. He added, however, “the green

hedges of Normandy are something I will never forget ! At the

junction of each hedge, there was an ambush !” Did

he speak about the enemy or the apple-brandy?

|

Thank you to ask for the author's authorization for a partial or complete publication of this narration

|

|